Improvement or Deterioration? Who decides “What is an improvement”?

The question of whether a patient has improved or deteriorated is fundamental to clinical practice [1]. To decide which treatment is the best, making decisions regarding prognosis and evaluating our management, we have to gain information. But let’s start at the beginning!

Usually patients, coming into our praxis, are searching for help (unfortunately they rarely show up for prevention advice). Our task, as health-care professionals is to identify their individual problems. But actually, each patient is his or her own subgroup of an individual problem, an individual goal and an individual way of achieving that goal. Cause everybody is so different and each problem has so many facets, we have to look at the “problem” in a multi-perspective way. Having only informations about the physio-diagnosis or a clinical pattern (e.p. disc-problem, shoulder-instability etc.) limits the ability to understand the whole picture and further on - to solve it. So, we need additional data on additional levels, for example of functioning and disability. There are different models we can use for identifying these different levels of an individual problem. One is the ICF (International Classification Functioning, Disability and Health). The ICF systematically groups different health and health-related domains for a given health condition. There are different components: 1) Body component – covers functions and structures of the body system; 2) Activity and Participation component – covers a range of life domains that people engage e.p. moving around, sports, daily-life-activities, work etc. [2]. As the functioning and disability of an individual occurs in a context, ICF also includes 3) a list of environmental factors [3].

So, during our assessment-process we try to find asterisks (data for re-assessment) for each component e.p. for Body structures (Inspection), Body functions (including psychological functions) – Pain (VAS), Impairments (Problems in body function) e.p. ROM measurements, Activity, Participation (Involvement in a life situation) and so on. In the Clinical Reasoning (CR) process, we use these data to make our re-assessment and to evaluate and control our treatments.

Chiu et al. [4] showed in their longitudinal study (6 months follow up) by analyzing 218 patients with chronic neck pain, that there are no strong correlations among disability, patient satisfaction, pain and physical impairments. Marks [5] shows, that there is moderate evidence, that the satisfaction of patient with hand problems is related to pain/symptoms, activity of daily living, aesthetics. But there are correlations for example for strength, range of motion and fulfillment of expectations.

These examples show, that for different problems, different individuals - different parameters are important to be satisfied in the meaning of solving an individual problem. Look at Picture 1 (title picture), ROM of shoulder ABD has objectively improved. But the patience perception, shown in the mirror, is a little sceptic. We can say, that….

The patients’ perception of a satisfactory outcome is influenced by numerous and individual factors.

We have different data for different constructs e.p. Pain, ROM, functional demonstrations, questionnaires addressing different facets of ONE problem. So actually, we are subdividing a complex picture into small pieces to be able to manage this complex-construct.

But – Which pieces are important to the patient? Or which piece is more important than others? Has the perspective about what is more important to the patient changed over time?

Let me make this point more clear by giving you a simple example:

Imaging having two patients in your praxis. Both have Low-Back-Pain (LBP). This pain occurs while bending down e.p. picking something up from the floor. Let’s say both patients have the same intensity in pain and the same impairments. So, for simplification purposes, we pick two constructs we want to measure – Pain (VAS) and ROM (Fingertip-to-Floor - FTF) of the spine. Now, one patient is a younger lady around her mid-twenties and the other patient is an older man in his early sixties. So, we take our baseline data (VAS, ROM) and treat our patients. After 4 weeks of treatment pain is still persistent (for some reasons ;O) but ROM is fairly good.

How will both patients react (remember, we are just pretending to have two parameters) on these changes? Do you think it will be the same?

So, the younger mother is able to bend down (FTF is good) but still, her back hurts. Even she’s able to pick up her baby, reaching down, she’s worrying about what’s going on, how longer will the pain persist, will it get worse, will she be able to handle the whole situation back home and so on. So the parameter pain, seems to be more important to her, than the parameter ROM.

She’s not very satisfied by the result (ROM doesn’t correlate with patient-satisfaction).

The older man has the same pain – but he’s happy. “I can handle the pain! I know sometimes it’s a little worse, sometimes a little better. But I can manage my daily life. When it gets worse I can lie down or I can rest. And the most important thing…I can play soccer with my grand-kids. And that’s more what my friends are able to do.”

He is satisfied by the result (ROM correlates with patient-satisfaction).

Remember, we just looked at only two parameters. It even gets more complicated, when considering even more parameters. This example shows, which construct is important to the patient, differs. Cause everybody is his own subgroup.

So, who decides what parameter is important to say, “if we are able to change this, that would be a good result!” Of course, we ask for the individual goals, but as I mentioned before, this goal usally gets formulated at the beginning of the therapy-process. But maybe the goal has changed over time. Maybe it was pain at the beginning, but now it is something else?! We can say, that the measurement of an outcome parameter is a critical step in the Clinical-Reasoning process. Cause it can mislead us.

So, wouldn’t it be great to have the possibility to have one assessment, one tool, easy to use to get an impression about the whole picture?

Guess what…there is ???? It’s called the….

GROC

The Global-Rating-Of-Change Scales.

The big advantage of this assessment is, that the patient conscious or subconscious is deciding what is important for him, for his individual problem. So the patient decides…..

What is the construct to be measured!!!! (instead of the therapist)

These scales are designed to quantify a patient’s improvement or deterioration over time, usually either to determine the effect of an intervention or to chart the clinical course of a condition [1]. It allows the patient to focus in on the concerns, which are most relevant to him or her.

The principal is easy:

Ask a patient to assess his or her current health status, recalling that status of a previous time-point, and then “calculate” the difference between the two [6].

The big advantage, as mentioned before is, due to the “global” aspect. This aspect distinguishes this scale from other outcome measurements, which are usually directed towards one specific dimension (construct to be measured) of the individual health status (e.p. pain, disability, work ability, ROM etc.).

For those of you, who want to get more detailed information I can recommend the paper from Kamper et al. [7]. For the rest…let’s take a short-cut, how to use this assessment.

There are two parts:

• Part 1 – The Question

• Part 2 – The Scale

Step 1- Formulating the Question

Things we should think about…

1) the health condition we are interested in, should be mentioned explicitly in the question (this becomes even more important, when comorbidities are involved).

Example: “With respect to your pain in your lower-back….”

2) Which wider-construct we are interested in? For example: satisfaction with outcome, self—assessed health-status or quality of life [8].

Example: “With respect to your pain in your lower-back, how satisfied are you with your condition….”

3) Providing an anchor for the scale. Means, the patient needs a time-point to compare with. Choosing a significant event will improve the ability of a patient to recall his or her health status [9].

Example: “With respect to your pain in your lower-back, how satisfied are you with your condition compared to the acute onset of your symptoms?”

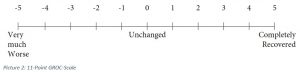

Step 2 – Designing the Scale

The range for the scale can vary. So, the secret is not to lose too much information (e.p. in a 3-point scale, better – same – worse) and give some meaning to the points on the scale to the patient, which wouldn’t be the case if the scale is too big . A 11-point scale offers the best compromise between patient preference, an adequate discriminative ability and test-retest-reliability (Picture 2) [10].

The ideal scale should be balanced, with equal numbers of points on either side of a midpoint named “unchanged”. The endpoints should also be labelled with written descriptions to give a meaning to the scale. Give the other points numbers, no words.

1) use a 11-point scale

2) name the midpoint “unchanged”

3) give the scale a meaning by labelling the endpoints with words.

4) use numbers for the rest of the scale.

There you also can see, that the Question and the scale itself, can vary from patient to patient to meet the individual aspects of their health-status. It’s like a tailor-made suit…it just fits the best compared to industrial wear (at least that’s what I guess, never had the chance to get a suit tailored for me ;O)

Lets collect all the advantages for the GROC-Scale….

10 - Advantages of the GROC-Scales [7]

1) flexible

2) quick

3) simple

4) charting self-assessed clinical progress

5) clinical relevant

6) adequate reproducibility

7) sensitive to change

8) intuitively easy to understand by the patient

9) patient can take into account, what is important for him or her

10) easy to evaluate

Some Clinical Properties

Don’t forget…

After all, that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t collect other outcome measurements. The GROC-Scales give only easy assessable and additional information about the individual health-status of the patient [7].

So, give it a go and hopefully it helps you and not to forget….

Our Patients!

Have a great week,

Mike

Literature

[1] Beaton (2000). Understanding the relevance of measured change through studies of responsiveness. Spine. 25: 3192-3199

[2] Giannangalo et al. (2005). ICF: Representing the Patient beyond a Medical Classification of Diagnoses. Perspectives in Health Information Management. 2: 7.

[3] WHO. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. 26.03.2017. 13:56

[4] Chiu et al. (2005). Correlation among physical impairments, pain, disability, and patient satisfaction in patients with chronic neck pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Vol. 86, Issue 3, P.534-540

[5] Marks, M. (2011). Determinants of Patient Satisfaction After Orthopedic Interventions to the Hand: A Review of Literature Journal of Hand Therapy. Vol.24, Issue 4, P.303 – 312

[6] Norman et al. (1997). Methodological problems in the retrospective computation of responsiveness to change : The lesson of Cronbach. J Clin Epidemiol. 50:869 – 879.

[7] Kamper et al. (2009). Global Rating of Change Scales: A review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. Vol. 17, No.3., P.163 – 170)

[8] Dworkin et al. (2005). Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 113: 9-19

[9] Guyatt et al. (2002). A critical look at transition ratings. J Clin Epidemiol. 55:900 – 908

[10] Preston and Colman (2000). Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psych. 104:1-15

[11] Costa et al. (2008). Clinimetric testing of three self-report outcome measures for low back pain patients in brazil: Which one is the best? Spine. 33:2459-2463

[12] Stratford et al. (1994). Assessing change over time in patients with low back pain. Phys Ther; 74:528-533.

[13] Watson et al. (2005). Reliability and responsiveness of the lower extremity functional scale and the anterior knee pain scale in patients with anterior knee pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther; 35:136-146

Comments