Clinical Relevance of Femoral Antetorsion and Acetabular Retroversion for the Treatment of Hip and lower Quadrant Impairments

Background:

There are several parameters describing acetabular orientation and femoral head asphericity in the current literature.

Abnormal femoral antetorsion and acetabular retroversion are two alterations amongst many others that also might be contributing factors in the development of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), hip osteoarthritis and low back pain.

Structural variations can lead to abnormal contact stresses within a physiological range of motion as seen in FAI, resulting in degeneration of the cartilage / labrum of the acetabulum and the early onset of osteoarthritis (OA) in young patients (Satpathy 2015)

The etiology of primary FAI remains controversial (Packer 2015) and the pathogenesis for idiopathic osteoarthritis has not yet been established.

Different studies show that morphologic changes at the femoral head and at the acetabulum are not rare among the asymptomatic population (Jung et al 2010, Schmitz et al 2013, Gosvig et al 2007).

Therefore it is essential to put more emphasis on clinical examination, based on history and physical findings than focusing on radiographic imaging alone (Reiman 2015).

The purpose of this blog article is firstly to define antetorsion of the femur and retroversion of the acetabulum.

Secondly to describe the clinical presentation and clinical tests described in the literature for these alterations in hip morphology and thirdly to discuss their clinical consequences for the assessment and treatment of lower quadrant impairments.

Definition of Femoral antetorsion

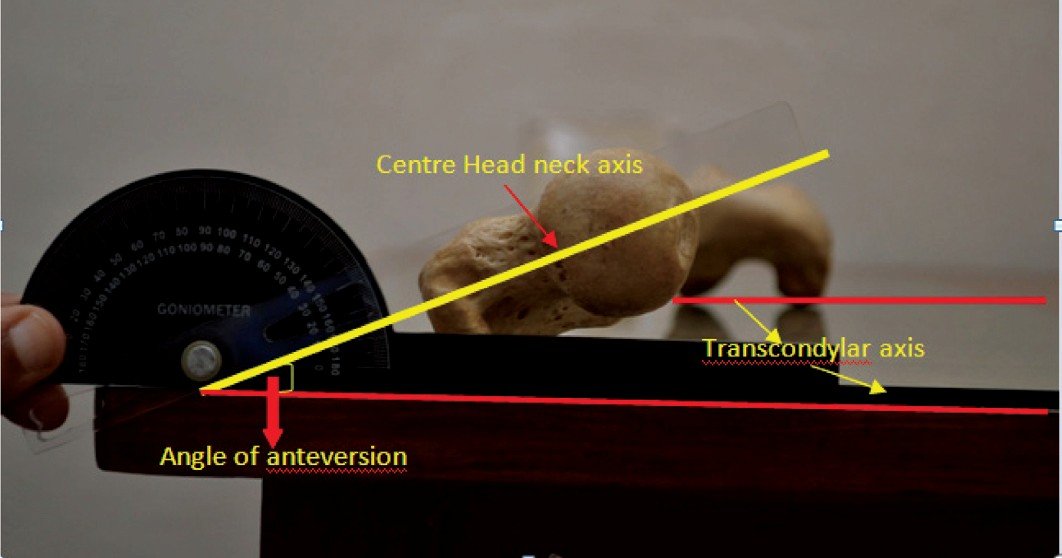

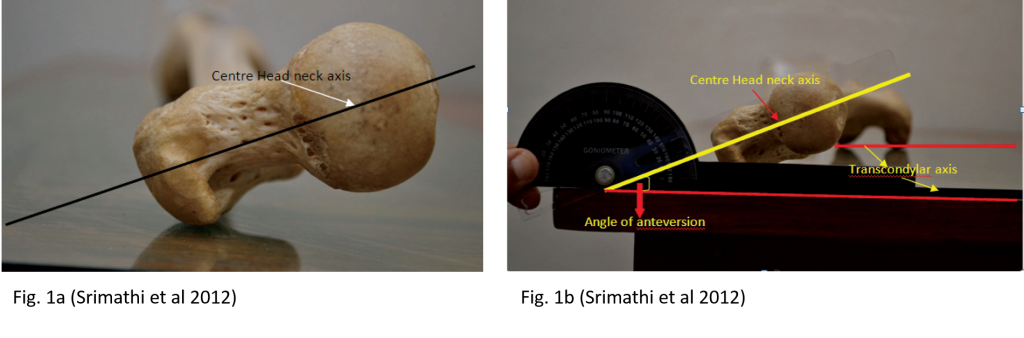

Femoral antetorsion describes the angle of the head and neck of the femur with respect to the femur shaft. The normal angle of torsion (AOT) in asymptomatic adults is described as 12,7° +/- 10 meassured by MR imaging in a study by Sutter et al 2012 (Figure 1a and Figure 1b)

In case of an increased AOT the result is a range of medial hip rotation that appears to be excessive, whereas the lateral rotation range appears to be limited.

A reduced AOT results in femoral retrotorsion. In that case the head and neck of the femur rotates posteriorly with respect to the shaft. The result is that the range of medial rotation appears limited, but the lateral rotation range appears excessive.

A study by Gelberman et al (1987) shows that structural antetorsion of the hip is present, when the asymmetry between medial and lateral rotation is present in 90° of hip flexion as well as in 0° of hip extension.

Definition of Acetabular retroversion

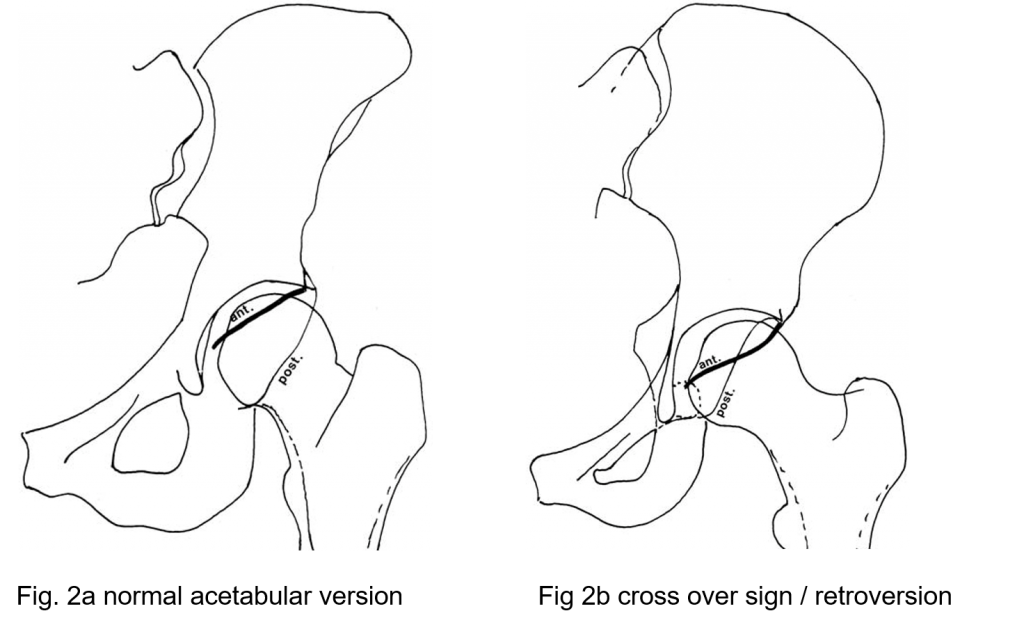

In the retroverted acetabulum the anterior edge of the mouth remains in a more lateral position than is normal, and the posterior edge is more medial. This is defined as either a positive cross over sign (the anterior wall of the acetabulum is more laterally than the posterior wall Figure 2a and 2b), or a positive posterior wall sign (the posterior wall of the acetabulum is more medial than the anterior wall) (Reynolds 1999).

Clinical presentation of altered AOT

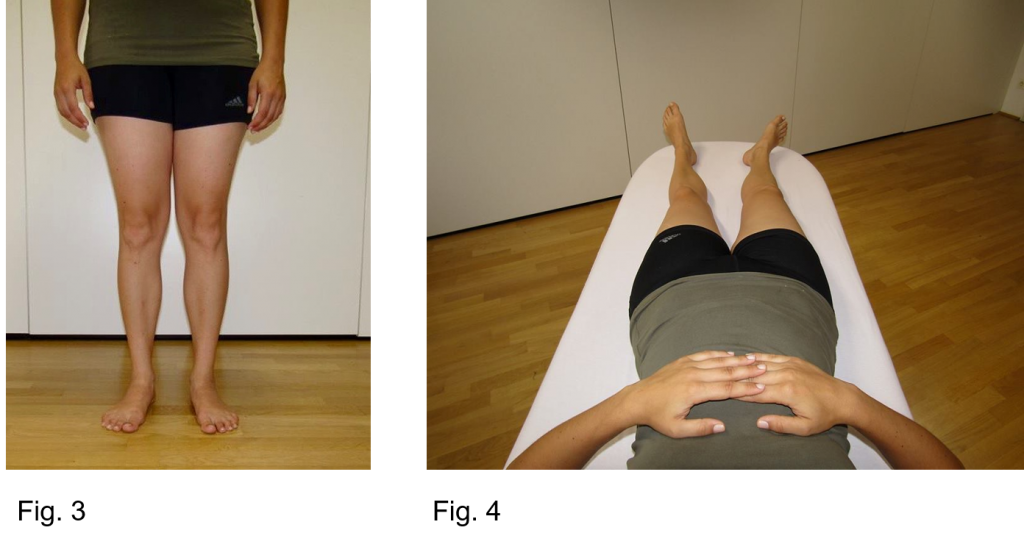

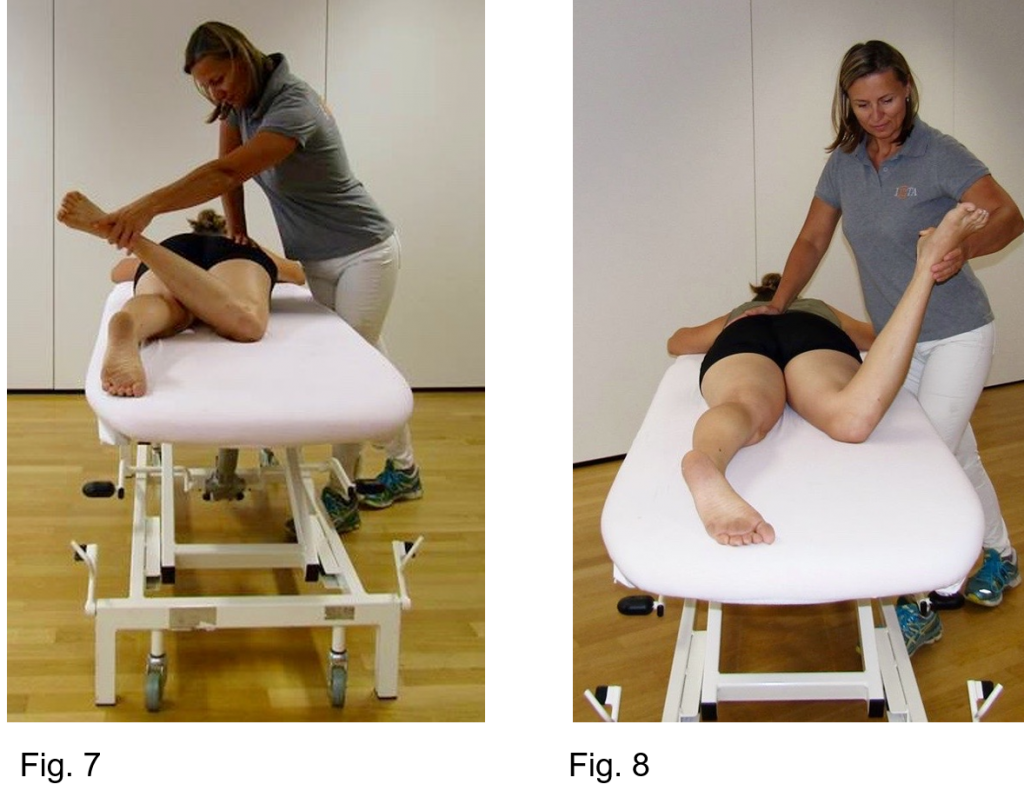

Figure 3-8 show physical examination findings that are indicative of femoral retrotorsion of the right hip.

Figure 3 shows a slightly external rotation of the whole leg in the natural foot forward stance position of the model.

In resting position in supine the right leg is also externally rotated (Figure 4).

Testing the internal and external rotation of the hip results in restricted internal rotation and excessive external rotation in 90° of flexion and in 0° of extension (Figure 5-8).

A biomechanical study by Satpathy et al (2015) showed that femoral retrotorsion increases peak joint pressure in the flexed position without evidence of cam lesion and the study authors conclude that it may act as a cause of FAI.

In Figure 9a and 9b the model demonstrates how deep she is able to squat until the onset of pain with a corrected unnatural symmetrical feet forward position (Figure 9a) compared to her natural more toeing out position with slightly external rotation of her right hip resulting in a much greater hip flexion angle (Figure 9b).

Behaviour

When patients with decreased antetorsion force their hips into a sustained position of medial rotation, or flexion/medial rotation, the hip may become painful, because of faulty alignment resulting in anterior irritation due to an increased pressure at the acetabular rim and femoral neck and excessive stretch posteriorly of the hip lateral rotators (Sahrmann 2002).

People with femoral retrotorsion prefer walking with there toes out, sitting with their legs crossed by resting their ankle on the opposite thigh or in the tailor seat position.

Pain aggravating positions or activities are: sitting with crossed legs (thigh over thigh), side lying position with hips in adduction and medial rotation, work or recreational activities requiring rotational motions (e.g., golf, soccer, ballet..).

It is reasonable to assume that the hip AOT has an influence on biomechanical movement patterns of the lower limb because of the consequent reduction in available range of hip internal or external rotation. During functional activities, adjusted movement patterns may need to occur in the kinetic chain to compensate for the restriction in hip movement (Tansey 2015).

The lack of hip medial or lateral rotation could cause the lumbar spine to become the site of compensatory motion.

As a clinical consequence the AOT has to be considered in the assessment and treatment of lumbar and lower limb impairments.

Clinical Tests

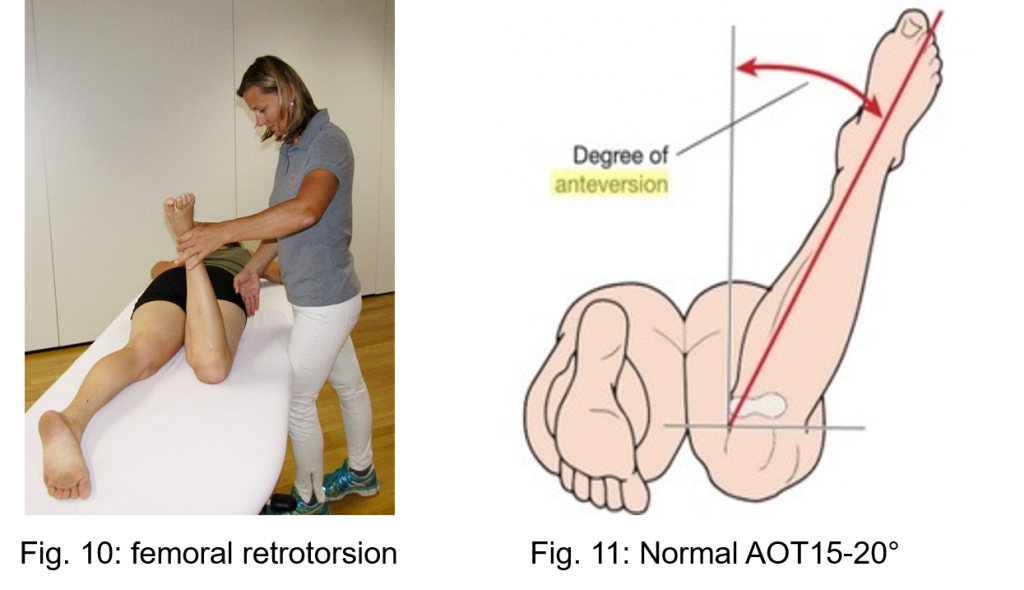

A clinical tool to measure the AOT is the Craig’s test (also called trochanteric prominence angle test / Ruwe’s Test) (Figure 10 and 11). The test is performed in prone position with the knee joint in 90° of flexion. The right hand is palpating the greater trochanter while the left hand internally and externally rotates the hip. At the point of maximum trochanteric prominence, representing the maximum distance between the femoral head and the trochanter, the angle between the tibia and the imaginary vertical axis can be measured by goniometer.

Figure 10 shows the tibia in an angle of 10 degrees medial to the vertical axis resulting in AOT reduction of about 30 degrees compared to a normal AOT angle of 15-20 degrees (Figure 11).

The Craig’s test was studied by Ruwe et al1992. The authors evaluated femoral antetorsion in 59 infantile hips with Craig’s test, radiographs and CT scans and compared the findings with intraoperative measurements. In this study Craig’s test had stronger correlations than CT scans and radiographs.

Souza et al (2009) compared the clinical measure of femoral antetorsion with MRI in eighteen healthy adults and assessed the intertester and intratester reliability. It was shown that the test exhibits substantial reliability (88 - 90%) and moderate agreement with MRI.

Furthermore Gelberman (1987) stated that there is a strong correlation between an increased AOT when internal rotation is exceeded and external rotation is limited in both, 90° of flexion and 0° of extension.

Clinical presentation of retroverted acetabulum

Reynolds and collegues (1999) studied clinically and radiologically 43 symptomatic hips with isolated retroversion of the acetabulum.

The results of the clinical findings in this study can be summarised as follows:

Symptoms:

- There is often a history of recent adoption of particular physical or sporting activities, or physically demanding occupation

- The progress from school to adult life-style is a vulnerable period

- Gradual onset of pain

- Pain in the groin, sometimes radiating to the thigh or knee and aggravated by activity

- Trochanteric pain

- Low back pain

Physical signs:

- alteration in the pattern of hip flexion in neutral line, may be limited to as 90°, progressing to full range only when allowed to move simultaneously into external rotation and abduction

- individuals tend to lie at rest in a position externally rotated at the hip

- external rotation in flexed position is more generous than usual

- range of internal rotation may be limited proportionally

- sitting on floor: patients are comfortable only with hips flexed, abducted, and externally rotated

Signs of impingement:

- once symptoms begin, there will be detectable signs of impingement

- Flexion, adduction and internal rotation, will reproduce distinct and repeatable discomfort.

Clinical Consequences and implications for treatment

- Retroversion of the acetabulum has many parallels in clinical presentation compared to decreased antetorsion of the femur

- The AOT has to be considered in the assessment and treatment of lower limb impairments and also in low back pain

Physical examination

- internal and external rotation of the hip should always be examined in 90° of hip flexion and 0° of hip extension

- Craig’s test should be used to confirm AOT

- Increased hip flexion with abduction in retroversion of the acetabulum and femoral retrotorsion

- Posterior translation of the femur may be increased and anterior translation decreased in retroversion of the acetabulum

- Passive physiological movements especially hip flexion, internal rotation and adduction could show a more bone to bone endfeel in femoral retrotorsion and in retroversion of the acetabulum

- Muscledysbalances have to be evaluated in the low back, pelvis and hip region

Treatment

- modify lower limb alignment to a more external or internal position in all closed kinetic chain exercises dependent on the structural variation

- adapt sporting and ADL activities (eg. Playing Golf, Squatting, climbing stairs, changing positions from sit to stand, from stand to sit...)

- avoid ADL’s in EOR F/IR

- adapt muscle strength tests and strengthening exercises to more external or internal rotation dependent on AOT for optimal muscle length and articular alignment

Conclusion

Structural variations in the hip that differ from mean values might not be pathologic abnormalities by themselves, but could contribute to the development of lower quadrant impairments.

The question is why do so many people with structural abnormalities stay asymptomatic and why do others develop symptoms.

Therefore the cause for the source to become painful is not lying in the bony system alone.

There are several factors that have to be considered in treatment: the mobility of neighbouring joints, the motor control system, correcting the lower extremity in unnaturel position over time, the load in history and in daily working or recreational activities with high impact or excessive rotation stress.

Identifying all contributing factors and underlying mechanisms is the great challenge for physiotherapists and manual therapists.

Maria Brugner-Seewald PT OMT-ÖVMPT, IMTA Teacher

References

Chadayammuri, V., Garabekyan, T., Bedi, A., Pascual-Garrido, C., Rhodes, J., OHara, J., Mei-Dan, O., 2016. Passive Hip Range of Motion Predicts Femoral Torsion and Acetabular Version. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 98, 127–134. doi:10.2106/JBJS.O.00334

Gelberman, R.H. 1987 Femoral Anteversion, A clinical assessment of idiopathic intoeing gait in children. J Bone Joint Surg 69-B, 75-79

Gosvig, K.K., Jakobsen, S., Sonne-Holm, S. 2010. Prevalence of malformations of the hip joint and their relationship to sex, groin pain, and risk of osteoarthritis. J Bone Joinj Surg Am 92, 1162-1169

Jung, K., Restrepo, C., Hellman, M., AbdelSalam, H., Morrison, W., Parvizi, J., 2011. The prevalence of cam-type femoroacetabular deformity in asymptomatic adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93, 1303–1307.

Packer, J.D., Safran, M.R., 2015. The etiology of primary femoroacetabular impingement: genetics or acquired deformity? Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. doi:10.1093/jhps/hnv046

Reiman, M.P., Thorborg, K., 2015. Femoroacetabular impingement surgery: are we moving too fast and too far beyond the evidence? British Journal of Sports Medicine 49, 782–784.

Reynolds, D., Lucas, J., Klaue, K., 1999. Retroversion of the acetabulum a cause of hip pain. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume 81, 281–288.

Ruwe, P., n.d. Clinical Determination of Femoral Anteversion.pdf.

Satpathy, J., Kannan, A., Owen, J.R., Wayne, J.S., Hull, J.R., Jiranek, W.A., 2015. Hip contact stress and femoral neck retroversion: a biomechanical study to evaluate implication of femoroacetabular impingement. Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery 2, 287–294. doi:10.1093/jhps/hnv040

Sahrman, S. 2002 Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. Mosby Verlag

Schmitz, M.R., Bittersohl, B., Zaps, D., Bomar, J.D., Pennock, A.T., Hosalkar, H.S., 2013. Spectrum of Radiographic Femoroacetabular Impingement Morphology in Adolescents and Young Adults: An EOS-Based Double-Cohort Study. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American) 95, e90 1. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.01030

Souza, R.B., Powers, C.M., 2009. Concurrent Criterion-Related Validity and Reliability of a Clinical Test to Measure Femoral Anteversion. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 39, 586–592. doi:10.2519/jospt.2009.2996

Srimathi, T., Muthukumar, T., Anandarani, V.S., Umapathy, S., Rameshkumar, S., 2012. A study on femoral neck anteversion and its clinical correlation. J. Clin. Diagn. Res 6, 155–8.

Tansey, P., 2015. Hip and low back pain in the presence of femoral anteversion. A case report. Manual Therapy 20, 206–211. doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.04.00

Comments

- {{ error[0] }}