What is manual therapy?

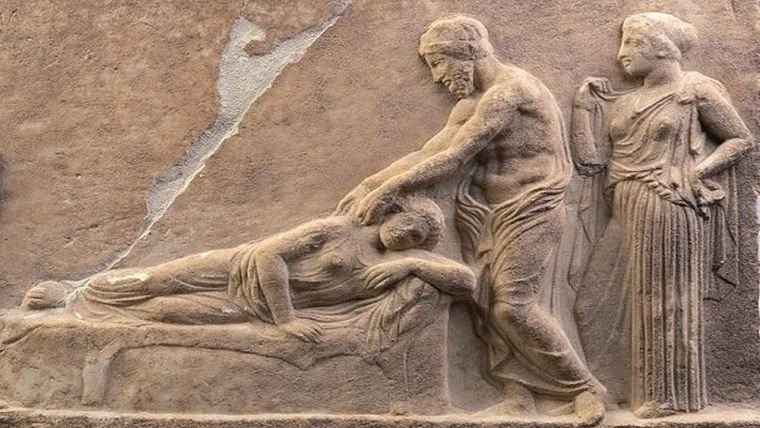

Have you ever thought about it? This question has probably never been so difficult to answer as at present. When I qualified as a physiotherapist it was easy. Manual Therapy was the mobilisation of joints using passive movement. That was not new. In fact, manual therapy is an ancient discipline that was mentioned as far back as Hippokrates (Pettman 2007). Physiotherapists have taught and have practised manual therapy for a least a century. But what do we mean by manual therapy? What do we actually do?

Definitions:

In the proceedings of a workshop, held in the USA in 1977, with contributions from such important early leaders in the field as Vladimir Janda, Karel Lewit and Sydney Sunderland, manual therapy was still on a passive track. They describe manual therapy as "the application of an accurately determined and specifically directed manual force to the body, in order to improve mobility in areas that are restricted; in joints, in connective tissues or in skeletal muscles". More recently Lederman was still describing manual therapy as "...the use of hands in a curative and healing manner or a hands-on technique with therapeutic intent..." (Lederman E. 2005).

Manual therapy is however evolving. Over the past few decades we have seen an enormous development in the field of manual therapy from a professional craft towards an evidence supported science. We are also seeing a broadening of the field of manual therapy to include exercises, education, pain sciences, communication skills and many more interventions.

In Gregory Grieve’s ground breaking book Modern Manual Therapy of the Vertebral Column from 1986 we already find a number of chapters dedicated to exercise. David Lamb states in this book that manual therapists “provide comprehensive conservative management for the spinal and peripheral joint pain of musculoskeletal dysfunction”. In fact, in the 4th volume of this standard work the title was changed to Grieve's Modern Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy (Jull et al 2015).

If we look at what IFOMPT has to say in their definition of manual therapy, which dates back to 2004, it states that we not only use manual techniques but also therapeutic exercises. Exercise can of course refer to auto mobilisation that mirrors our passive treatment. However, the use of active strategies to influence any motor control and muscle balance deficits which may be contributing to the patient’s problem are also implicated. IFOMPTs educational Standards Document clearly describes exercise prescription as one of the skills or competencies necessary in an OMPT educational programme (https://www.ifompt.org/Educational+Standards.html)

If we look at what IFOMPT has to say in their definition of manual therapy, which dates back to 2004, it states that we not only use manual techniques but also therapeutic exercises. Exercise can of course refer to auto mobilisation that mirrors our passive treatment. However, the use of active strategies to influence any motor control and muscle balance deficits which may be contributing to the patient’s problem are also implicated. IFOMPTs educational Standards Document clearly describes exercise prescription as one of the skills or competencies necessary in an OMPT educational programme (https://www.ifompt.org/Educational+Standards.html)

So the more comprehensive view of manual therapy has been around for a long time with some concepts embracing it earlier than others. Indeed, some authorities are racing ahead and are in danger of losing manual therapy skills and some still seem to adhere to the old definitions.

“When the scientific literature is considered, attributing successful spinal manipulative therapy outcomes solely to the identification and correction of biomechanical faults makes as much sense as crediting a beard for winning a hockey playoff series". Joel Biolosky.

Geoff Maitland was prone to saying that if we look after the joints the muscles will look after themselves. This may be true and we can often observe a change in muscle activity following mobilisation or manipulation. Take a look at Pieter Westerhuis treating hip weakness through a spinal manipulation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qzxzzjN_eQ. More recent work investigating Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition (AMI) is helping us to understand some of the mechanisms behind this (Freemann, Mascia, McGill 2013, Rice and McNair 2010, Sonnery-Cottet et al 2019, Lepley AS and Lepley KL 2021, Norte et al 2021). Unfortunately, this assumption does not always hold true. We often need to address muscle function directly. Passive manual therapy interventions, however, often provide us with an important window to enable an earlier activation of muscles or a quicker progression of exercises and thus facilitate rehabilitation. This effect should not be underestimated.

More recently Rhon and Deyle (2021) have furthered a lively debate with their discussion. They argue that “… manual therapy describes a wide variety of treatments, some with passive components and some that are primarily passive in certain scenarios. But manual therapy can be an integral part of highly active treatment strategies…... This Viewpoint challenges the assumption that manual therapy is always a passive treatment of low value”.

Indeed, it can be argued that “when people talk about manipulative treatment it seems impossible to avoid the problem of their putting inordinate emphasis on (passive) techniques” (Maitland et al 2005).

If we see manual therapy as a purely passive concept we are missing the whole patient picture and thus will miss important aspects of management. We are then in danger of seeing manual therapy as a collection of techniques and not as a “specific concept of thought and action” Hengeveld and Banks (2014).

So what’s in a name:

There have been a number of names for what we do over the years. Manipulative therapy, manual therapy, orthopaedic manual therapy, manipulative physical therapy. All of these names unavoidably lead to the impression that we still only use passive hands on techniques. Therefore, the term “musculoskeletal physiotherapy” would seem to better reflect what we do.

Of course the word “manual” derives from the Latin “Manus” meaning "hand" or "of the hand". Brilliant minds have been responsible for developing various concepts and schools of manual therapy which are rooted in the application of techniques using the hands. Such game changing names as James Cyriax, James Mennell, Freddie Kaltenborn, Olaf Evjenth, Stanley Paris, Geoff Maitland or Robin McKenzie and Brian Mulligan come to mind to name but a few.

In fact, the IFOMPT member organisations led a lively debate last year about whether they should rename the federation from “International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists” to the “International Federation of Orthopaedic Musculoskeletal Physical Therapists. They were, however, unable to come to a global consensus.

In fact, the IFOMPT member organisations led a lively debate last year about whether they should rename the federation from “International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists” to the “International Federation of Orthopaedic Musculoskeletal Physical Therapists. They were, however, unable to come to a global consensus.

So what do I think?

I once learned that writing in Block capital was like shouting, so here we go I am going to shout!

I believe we need to change the name of what we do. We are the experts in “MUSCULOSKELETAL PHYSIOTHERAPY”. This reflects current practice. We need to TAKE ON ALL THE NEW INPUT AND EVIDENCE WITHOUT LOSING OUR OWN UNIQUE SKILLS OF MOBILISATION AND MANIPULATION. Having been in “the trade” for a while now I have seen many trends reach a peak and later either disappearing or finding an appropriate place in our daily clinical life and teaching. MOBILISATION AND MANIPULATION ARE MUCH MORE THAN A TREND _ LET'S KEEP THEM.

The bottom line: Change the name but DON’T LOSE OUR MOBILISATION AND MANIPULATON SKILLS!

And what do you think?

Please let us know

Literature:

Freeman S., Mascia A., McGill S. Arthrogenic neuromusculature inhibition: a foundational investigation of existence in the hip joint, Clin. Biomech (Bristol Avon) 2013:28(02):171-7

Grieve G. Grieve’s Modern Manual Therapy of the Vertebral Column. Churchill Livingstone, 1986Edinburgh, London

Hengeveld E., Banks K (2014) Maitland’s vertebral manipulation: Management of neuromusculoskeletal Disorders – Volume 1 (8th Ed) 2014. Elsevier Edingburgh, Lo

Rhon D., Deyle GD. Manual Therapy: Always a PassiveTreatment? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2021;51(10):474–477. Epub 1 Jul 2021. doi:10.2519/jospt.2021.10330

Jull G., Moore A., Falla D., Lewis J., McCarthy C., Sterling M (Eds) Grieve’s Modern Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy 4th Ed. 2015. Elsevier, London, New York.

Korr I.M. (Ed) The Neurobiologic Mechanisms in Manipulative Therapy. Plenum Press, 1978. New York

Lederman E. The Science and Practice of Manual therapy. 2nd ed. 2005. Elsevier: London.

Lepley AS., Lepley KL. Mechanisms of Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition J Sport Rehabil 2021; 1:1-10.

Maitland G., Hengeveld E., Banks K., English K. (Eds) Maitland’s Vertebral Manipulation (7th Ed) 2005. Elsevier Edingburgh, London.

Norte G, Rush J, Sherman D. J. Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition: Best Evidence, Mechanisms, and Theory for Treating the Unseen in Clinical Rehabilitation. Sport Rehabil. 2021; 9:1-19

Pettman E. A history of manipulative therapy. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2007; 15(3):165-75

Rice DA, McNair PJ. Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: neural mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2010;40(03): 250-66

Sonnery-Cottet B., Saithna A., Quelard B., Daggett M., Borade A., Ouanezar H., Thaunat M., Blakeney W.G. Arthrogenic muscle inhibition after ACL reconstruction: a scoping review of the efficacy of interventions British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53(5):289-298.

Comments