I have a good rapport with my patients – should I bother about a therapeutic alliance?

Elly Hengeveld, MSc, B.Health (PT), OMPTsvomp, Clin. Spec. MSK PhysioSwiss, IMTA senior teacher

This blog is an extract from: Hengeveld & Silvernail, Communication and the therapeutic relationship. In: Hengeveld & Bucher Dollenz. Principles Of The Maitland Concept Of NMSK Physiotherapy, Vol. 1, 9th ed

(submitted for publication)

Contents of this blog:

1.1. Introduction to therapeutic alliance

1.2. Biopsychosocia paradigm

1.3. Intersubjectivity

1.4. Person centered care and pain

1.5. Characterisctics of a therapeutic alliance

1.6. Research & therapeutic alliance

1.7. Shared Decision Making

1.8. Research & shared decision making

1.9. Miciak’s framework of the physiotherapeutic alliance

1.10. Conclusion

1.11. References

1.1 Introduction to therapeutic alliance

Most, if not all, physiotherapists join the profession because they like to work with people. Naturally, with this attitude, they will be able to build up a good rapport with their patients with an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. In the last years, numerous publications about the therapeutic alliance can be found in physiotherapy literature, and therapists may wonder, why they would need more reflection about the therapeutic relationship.

This blog gives on overview of characteristics of a therapeutic alliance with an encouragement to our clinician readers to reflect upon those aspects which they naturally express in their daily practice, and which elements may need further consideration or development.

|

Description of therapeutic alliance The therapeutic alliance is described as the working relationship between patients and therapists, based on a positive connection through collaboration, communication, therapist empathy and mutual respect (Babatunde, MacDermid, & MacIntyre, 2017). The therapeutic alliance is a dynamic aspect of the therapeutic process, with communication as the dominant mediator. It is influenced by both the client and the therapist with biological, social, and psychological contributing factors (Søndenä, Dalusio-King, & Hebron, 2020). The psychologist Carl Rogers (1980) had a major influence on the awareness of therapeutic relationships with a person centered attitude. Numerous studies have been undertaken since Rogers’ publications about person-centered practice, with the viewpoint on person-centeredness as a tool to enhance individual responsibility for health. Also, person centered approaches to clinical practice respect the autonomy of individuals which allows them to take part in decisions in their care and treatment options. Rogers (1980) postulated that the (therapeutic) relationship between clinicians and patients is fundamental to a process of motivation and change, in which patients’ individual experiences with the individual needs, thoughts, feelings, meanings and contextual elements are leading factors. Rogers described the following principles of a person-centered attitude: · Empathy: · Unconditional regard: · Congruence (Authenticity / genuineness): Rogers viewed the art of (active) listening as the most powerful tool to enhance relationships. However, he emphasized that well developed conversation and questioning skills accompany good listening skills (Owen, 2022) |

1.2 Biopsychosocial paradigm

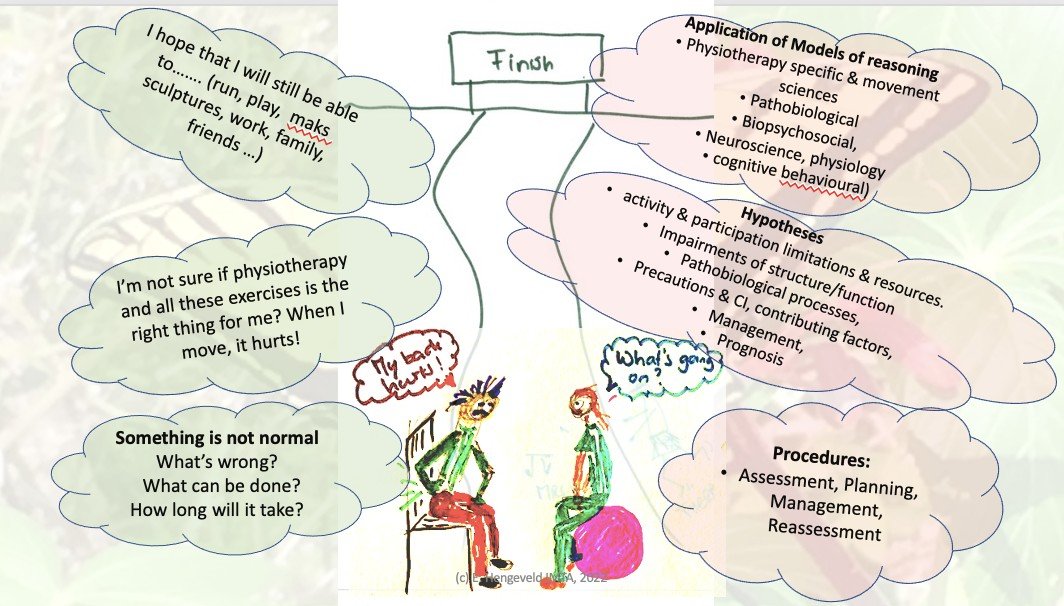

Each patient has a unique frame of reference, with thoughts, beliefs, emotions and feelings, values, socio-cultural context, and individual biography. All these aspects and more may be of substantial influence how persons act, react, and process experiences in their lives. For physiotherapists it is recommended to reflect on these aspects as potential contributing factors to the patient’s symptoms and functional limitations (as the “owner of the umbar spine”), and to address these factors constructively in the therapeutic process.

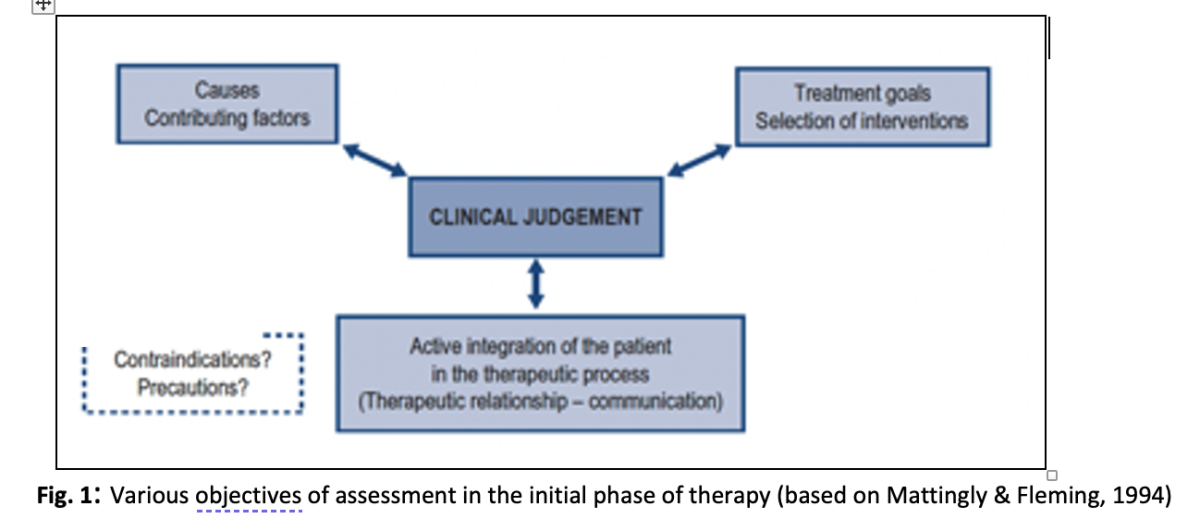

When embarking on the therapeutic process, physiotherapists need to develop hypotheses regarding causes and contributing factors to the client’s plight, as well as optimum management strategies. Furthermore, it is crucial to actively integrate patients into their therapeutic process (Mattingly & Fleming, 1994). (See Fig. 1). To achieve the latter, a humanistic, person-centered approach to treatment with caring for the therapeutic relationship (“alliance”) and deliberate communication skills is prerequisite.

It appears that many physiotherapists develop a person-centered attitude to their patients over the years of clinical experience, albeit it often more on an intuitive level. Jensen, Gwyer, Shepard & Hack (2000) observed that expert physiotherapy practice distinguishes itself from advanced physiotherapists, with a client-centered knowledge base developed by regular reflection about the therapeutic process and interactions, collaborative problem-solving with the client, and an attitude of caring and commitment to patients.

|

Reflection tip: · How do you see your person-centered knowledge base? · Do you often reflect about the therapeutic process and the interaction of/with your client? · What does collaborative problem-solving mean to you? · How do you consider your leadership and coaching role with your patient? Would you tend to be more directive in your communication, or would you prefer to guide by asking questions and active listening? |

1.3 Intersubjectivity

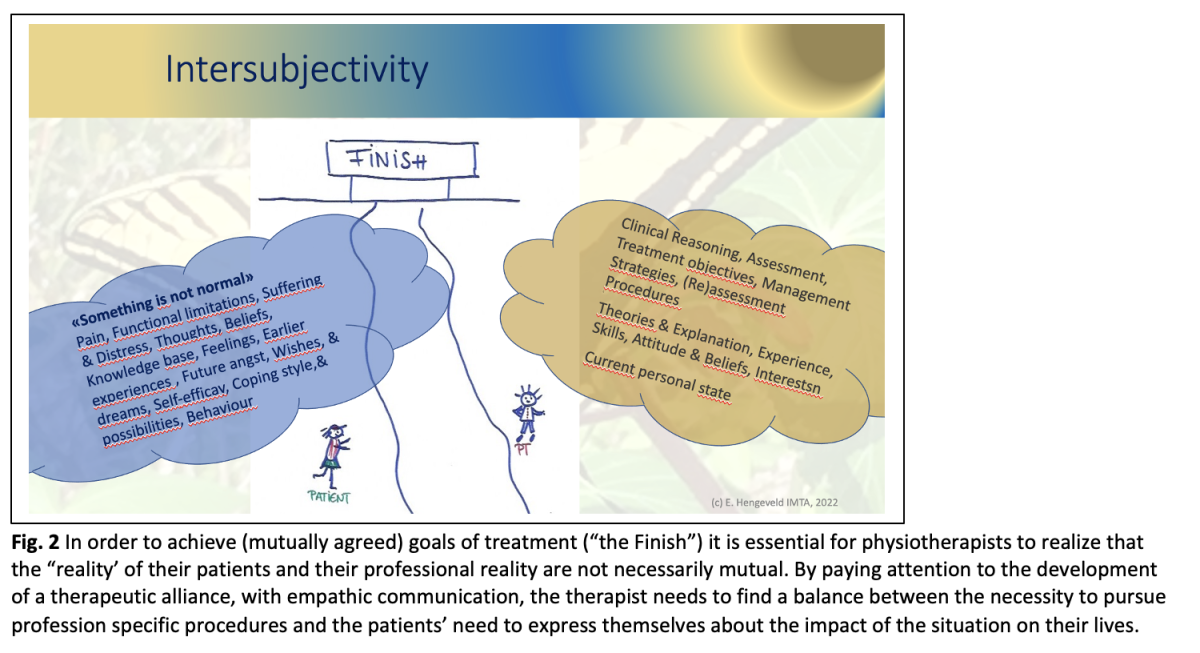

When patients and physiotherapists engage in the therapeutic process, they start to share an intersubjective experience, which is described as follows (Leeming, 2014):

“An interchange of thoughts and feelings, both conscious and unconscious, takes place between two persons or “subjects”, as facilitated by empathy. To understand intersubjectivity, it is necessary first to define the term subjectivity, i.e. the perception or experience of reality from within one’s own perspective (both conscious and unconscious) and necessarily limited by the boundary or horizon of one’s own world view”

· Power imbalance in assessments

In a discourse analysis of the interactions between medical doctors and patients, Wodak (1997) observed a predominant clinician-centered discourse that is mostly related to the clinician’s professional, diagnostic tasks. She noted a power imbalance between the “realities” of the medical doctor and the patient, in which doctors need to arrive as quickly as possible at a diagnosis, while patients often want to explain aspects of their biography and the impact of their symptoms or illness on their lives (Wodak, 1997).

A similar power imbalance may also occur in physiotherapy practice. Both physiotherapist and client will enter the therapeutic encounter with their reality of individual perspectives (fig. 2). On the one hand, patients may seek the help of a physiotherapist, because they feel that “something is not normal”, which is of particular concern to them and their lives. On the other hand, physiotherapists naturally will primarily follow the professional requirements of assessment and management procedures. However, it is suggested to incorporate a client-centered, narrative approach into the physiotherapy specific procedures, with attention to the development of a therapeutic alliance to prevent the power imbalance of a predominant therapist-centered agenda (Moore & Jull, 2012) (CSP, 2020).

A person-centered agenda should allow patients to give their account of their individual experiences without controlling patients with too strict assessment criteria, in which they may only be allowed to talk about those aspects which are relevant to physiotherapeutic diagnosis and treatment planning from the perspectives of the physiotherapists. (Thomson, 1998).

1.4 Person centered care & pain

The concept of person-centered care is increasingly accepted within physiotherapy as a general attitude. However, it appears that the translation of person-centered principles, with inclusion of psychosocial aspects into clinical practice is challenging for physiotherapists (Derghazarian & Simmonds, 2011) (Naylor, Killingback, & Green, 2022).

In an observational study among eight physiotherapists offering low back pain education, Trede et al (2000) concluded that only one participant followed a person-centered approach, with active listening to the needs of the patients, while the remaining physiotherapists, who thought to adhering to a person-centered approach, in fact followed a predominant therapist-centered approach.

In a study on empathy, it was discussed that physiotherapists appeared to be more concerned with data-gathering in the first treatment session and showed more empathy in the second session than in the first (Thomson, Hassenkamp, & Mansbridge, 1997).

Daluiso-King & Hebron (2020) discussed that some physiotherapists oversimplify the bio-psycho-social model by compartmentalizing the bio, psycho and social elements and viewing it in a reductionist, dualistic philosophy. Physiotherapists seem to consider the model within two entities, in which biomedical aspects are separated from psychosocial dimensions. Furthermore, they describe that physiotherapists may not always feel confident with dealing with psychosocial aspects due to an incomplete conceptualization of the bio-psycho-social model. Also (Hutting, Oswald, Staal, & Heerkens, 2020) noted in a qualitative survey that physiotherapists in the Netherlands appeared to feel more comfortable with providing information about biomechanical and physical factors of a patient’s condition for self-management strategies than psychosocial factors.

|

Empathetic acknowledgment of the individual experience of the patient, is probably one of the most important characteristics of the first step in the development of a strong therapeutic alliance.

Intersubjectivity as “bridge building”: · Clinicians show sincerely interest for the narrative of the individual experience of their patients and acknowledge this experience · Clinicians explain to patients why they take certain steps in assessment procedures, to gain understanding from the patient and a commitment to the therapy process (e.g. by engaging in reassessment procedures) |

1.5 Characteristics of a therapeutic alliance

In defining the characteristics of a therapeutic relationship, Rogers worked mainly with the characteristics and behaviors of the therapist. In addition, the psychotherapist Bordin (1976, 1980 cited by (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989)concentrated on the concept of mutuality as a primary element of a therapeutic alliance. Bordin defined three constituent components, which define the quality and strength of all alliances:

- · Bonds: relates to the complex network of positive personal attachments between client and therapist based on trust, acceptance, and confidence

- · Goals: clients and therapists collaboratively clarify goals, which are meaningful to the client

- · Tasks: mutual agreement of interactions and interventions, which both partners in the alliance perceive as efficacious and relevant in achieving the goals

Babatunde, MacDermid and McIntyre (2017), in an extensive literature review about the characteristics of the therapeutic alliance, categorized eight core elements, with several rankings of represented studies. They suggest to specifically address these themes in future research and to implement them in undergraduate education of physio- and occupational therapists (Table 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of the therapeutic alliance (Babatunde et al, 2017)

|

Theme |

Specifics |

|

· Congruence |

o Agreement on goals o Problem identification o Agreement on tasks |

|

· Connectedness |

o Perceived good relationship o Friendliness o Empathy o Caring o Warmth o Genuine interest/concern o Therapist’s faith / belief in client o Honesty (Genuineness) o Courtesy |

|

· Communication |

o Non verbal o Listening skills (active listening) o Visual aids o Clear explanation and information o Positive feedback |

|

· Expectations |

o Therapy o Outcomes |

|

· Individualized therapy |

o Responsiveness (to personal circumstances) o Holistic practice (related to individual circumstances & context) |

|

· Influencing factors |

|

|

· External factors |

o Structures, processes and environment o Planning of care |

|

· Therapist prerequisite |

o Skill, competence and experience o Humor o Life experiences o Emotional intelligence |

|

· Client prerequisite |

o Personal characteristics o Existing resources o Life experience o Willingness to engage |

|

· Partnership |

o Trust / dependability o Respect o Mutual understanding o Knowledge exchange o Power balance o Active involvement/ engagement |

|

· Roles and responsibilities |

o Activating patients’ resources o Motivator/encourages o Professional manner o Educator/Advisor/Guide o Active follow-up o Autonomy support |

1.6 Research and the therapeutic alliance

Several studies with patients exploring their experiences with the therapeutic relationship, showed that patients valued the following in a therapeutic relationship:

- Initially patients had expectations about exercises, diagnoses, clear information about assessment and diagnosis, advice and reassurance (Unsgaard-Tøndel & Søderstrøm (2021) Kamper et al (2018). However, after some sessions with the therapist, they especially valued the therapeutic relationship with the following building block, which enhanced their understanding and motivation to adhere to advice and self-management:

o Active listening

o Individual tailoring

o Continuous monitoring

o Adjustment of treatment

o Empathetic communication

o Sufficient time with the therapist.

In Kamper et al’s study it was remarkable that over 50% of the participants expressed the need to

discuss the impact of their pain on their lives.

- Also, patients perceived a stronger therapeutic alliance, when clinicians’ interaction styles facilitated patient interactions, such as exploring the patient’s individual illness experience, listening carefully and addressing emotional issues. Especially the discussion of options, asking patients’ opinions, encouraging questions and answering, explanations of what patients needed to know were of positive influence. Advice and giving directions were significantly negatively associated with a therapeutic relationship. Pinto, Ferreira, Oliviera et al (2012)

- Among similar factors as mentioned above, (Bishop, et al., 2021) concluded that a therapeutic alliance is also enhanced by organizational matters, such as appointment procedures, waiting times, organization and facilities

- In a mixed-methods study with patient- and therapist questionnaires and observations of videotaped first session, (Myers, et al., 2022) noticed that a perceived stronger therapeutic alliance showed an immediate effect on pain scores, albeit it with a ceiling effect after one month. However, when the therapeutic relationship improved over the month, pain and function had a tendency to further improve. Interesting, was that clinical variables such as *lack of human touch, *missing information / education, and *not reflecting back to client were significantly associated with lower ratings of therapeutic alliance. On the other hand, *pausing to listen, *using humor, *transitions, *use of open questions, and *clarifying questions were some of the top behavioral practices associated with higher patient perceived therapeutic alliance. Using patient-centered communication strategies throughout a clinical encounter appears to build stronger therapeutic alliance

- It appears that a perceived strong therapeutic alliance linked to treatment outcomes such as

- Treatment adherence (persons with brain injuries or multiple pathologies; adults with chronic MSK pain)

- Depressive symptoms (persons with cardiac symptoms)

- Treatment satisfaction (persons with musculoskeletal conditions)

- Function (geriatric persons, individuals with chronic pain or lumbar pain)

Based on (Hall, Ferreira, Maher, Latimer , & Ferrreira, 2010) (Kinney, et al., 2018) (Alodaibi, et al., 2021) (Moore, Holden, Foster, & Jinks, 2019)

- Immediate effects on NRS of perceived pain (Myers et al, 2022), Fuentes et al (2014

- Effects on self-efficacy, perceptions and beliefs about LBP and psychosocial distress (Bishop et al, 2021).

1.7 Shared decision making

The concept of mutual agreement or congruence of goals, tasks and bonds is essential in person-centered approaches. (Bordin, 1976, cited by Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) (Babatunde, MacDermid, & MacIntyre, 2017). The term “shared decision making” is increasingly used in professional literature and is an expression of collaborative reasoning (Edwards, Jones, Higgs, Trede, & Jensen, 2004).

“Shared Decision Making” (SDM) is placed in the context of changes in healthcare, with increased focus on empowerment of patients, ethical practice of informed consent, patient rights, collaboration, respecting autonomy of the persons seeking care (Hoffmann, et al., 2014) (Stiggelbout et al, 2012).

Participation in decisions should guide patients to maintain optimum control over the decisions and actions related to their health care (WHO, Health promotion glossary, 1998). It provides a balance to paternalistic power structures and can be seen as an encounter between experts: the clinicians with their expertise on the one hand, and patients as experts in their own lives on the other hand (Godolphin, 2009).

(NICE, 2017) describes the process of shared decision making as follows:

Shared decision making is a collaborative process that involves a person and their healthcare professional working together to reach a joint decision about care. It could be care which the person needs straightaway or care in the future, for example, through advance care planning. It involves choosing tests and treatments based both on evidence and on the person's individual preferences, beliefs, and values. It means making sure the person understands the risks, benefits, and possible consequences of different options through discussion and information sharing. The joint process empowers people to make decisions about the care that is right for them (with the options of choosing to have treatments or not changing what they are currently doing included).

(Hoffmann, et al., 2014) emphasize that shared decision making is a continuous process within the framework of patient-care and not a single moment in the clinical encounter.

- Differences in emphasis of decisions in medicine and rehabilitation

In medical practice, shared decision making is mostly dealing with the options, risks, and benefits of examination and treatment with various biomedical diagnoses (Hoffmann, et al., 2014, p. 2).

In rehabilitation practices, such as physio- and occupational therapy, the process of shared decision making involves predominantly decisions about (Hengeveld & Banks, 2014)

· meaningful goals of treatment

· meaningful interventions leading to the mutually agreed goals.

· parameters with which both patient and therapist monitor progress in the treatment process and the outcomes of the various treatment-interventions

It is remarkable that this difference in accentuation of shared decision making is not yet considered in current descriptions of shared decision-making processes.

The implementation of shared decision-making processes appears to be limited in numerous clinical domains, in spite of general acknowledgement of the value of its concept in practice.

However, a lack of opportunity to take part in decisions may have a profound impact on the lives of some patients:

(Hack, Degner, & Watson, 2006) investigated the situation of women with breast cancer, three after their treatment. With questionnaires they investigated how the women perceived the shared decision-making processes in the diagnostic and treatment phases of their care. Those women who were more involved in the decision-making process, perceived a better quality of life, less fatigue, significant better physical and social functioning than the women who perceived less involvement in the process. In retrospect, the latter group regretted that they were not given the opportunity of participating in the decisions about their care.

1.8 Physiotherapy research in shared decision making

· In a randomized clinical trial with 75 patients with chronic low back pain, (Gardner, et al., 2019) showed that patient education in combination with shared decision-making processes led to better functional outcomes (n=37) than in the control group (which received a standardized exercise program n= 38). Primary variables were pain intensity, functional limitations. Secondary variables included quality of life, fear avoidance behavior, depression, self-efficacy, anxiety, and stress. These variables, including health care use were evaluated after 2, 4 and 12 months respectively. After 12 months the primary variables, as well as quality of life, fear-avoidance behavior and self-efficacy remained significantly better in the intervention group than in the control group. Only small effect sizes were observed in anxiety, depression and stress. No changes were observed in health care usage.

· It has been recognized, that the congruence between patient- and therapist goals is often mismatched, and shared decision making processes tend to be underutilized (Moore & Kaplan, 2018) (Dierckx, Deveugele, Roosen, & Devisch, 2013):

In a systematic review of 15 articles about shared decision making and goalsetting in rehabilitation settings, (Rose, Rosewiliam, & Soundy, 2017) concluded that only two articles were related to patient-centered decisions, while the other studies showed that only partially participative decisions were made. However, in all studies clinicians and patients agreed upon the advantages of shared decision making. Patients in four studies noticed a sense of ownership and control over their own therapeutic process, feeling more motivated and at eye-level with therapist. They especially appreciated treatment goals and interventions, which were adapted to their unique situation. Therapists experienced similar barriers and misconceptions as mentioned by (Hoffmann, et al., 2014), but they agreed that shared decision-making processes promote patient-motivation

· (Leach, Cornwell, Fleming, & Haines, 2010), in semi-structured interviews with physiotherapists, noticed that most therapists defined treatment-goals on impairment levels (WHO, 2001) based on their physical examination. The goals on activity levels were not discussed to explore the meaningfulness from the patient’s perspective.

· In a study with ten physiotherapists and 21 patients with hemiplegia, (Parry, 2004) analyzed 74 audiotaped sessions. There were only eight sessions in which therapists guided a shared decision -making process about goalsetting. Time constraints, challenges in the patient-interactions as well as situations with a poor prognosis made it difficult for the therapists to optimize collaboratively made decisions.

- However, levels of education and specific training in shared decision making appears to optimize the process (Couët, et al., 2015) , (Hausherr, Suter, & Kool, 2020).

1.9 Miciak’s framework of the physiotherapeutic alliance

Miciak (2015), in semistructured interviews with 11 physiotherapistis and 7 patients, developed a conceptual framework of the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy. She recognized that many insights about therapeutic relationships are based on psychotherapy practice. However, little is known how bonds are developed and which conditions make the foundation of a constructive therapeutic relationship within physiotherapy practice. The therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy practice has some unique features which distinguishes itself from other professions. For example, using touch in assessment and treatment, which is less likely in psychotherapy practice; more time spent over several consecutive meetings with patients in contrast to consultation times with medical doctors; patients often working with the same therapist, allowing for the development of a consistent relationship, compared with e.g. nurses who change shifts.

The framework encompasses the following components which are prerequisites of a therapeutic alliance:

a) Conditions of engagement: (Miciak, Mayan, Brown, Gross, & Joyce, 2018b):

- Presence

(e.g. recognizing that a patient may need more 1:1 time, in spite of a hectic schedule; remaining focused

on the patient in spite of busy case load or personal stressors. Patients needing to feel the treatment and

learning to understand their reactions).

- Receptive

(e.g. entering interactions with an open attitude to negotiate appropriate treatment plans and a

focused receptivity to identify salient issues and needs. Allowing patients to tell their story can be

important to create a safe and receptive atmosphere).

- Genuine

(e.g. being yourself in a warm and caring way; directness, with being clear and fortright in a tone

conveying concern or compassion; investing In the personal by showing authentic interest in the person

and willingness to disclose something about one self).

- Committed

(e.g. therapist and patients committed to understanding of patient’s situation and understanding each

other’s roles; committed to action – engaging to achieve goals, “buying into” therapy and

reassessments).x

b) Ways of establishing connections (defined as “a link to another person based on common ground or acknowledgement” (p. 4):

- Acknowledging the individual

(e.g. meeting as an equal human being (not only as a “back”), with a life with many experiences outside

of the treatment room; Greeting with smile, shaking hands, engaging in a brief small-talk at the first

meeting to establish a first connection; Physiotherapists ensuring that the patients are being seen, heard

and appreciated; “In-the-moment” validating or acknowledging patients’ experiences when they emerge)

- Giving-of-self

(e.g. If needed, physiotherapists spending more time or energy with/for the patient; physiotherapists

indicating that they want to review some literature, consult a colleague, or saying that they were thinking

of the patient’s case when attending a seminar; Sincerely showing empathy, or checking-in on the

patient; If appropriate, some self-disclosure about things or topics they had in common with the patients).

- Using the body as a pivot point (respecting the patient’s bodily experiences and helping them

to become aware and (re)connecting with their bodies, within a biopsychosocial paradigm)

(e.g Clarifying physical problems and solutions [movement related, and others such as a sense of tension;

facilitating the patient’s connection to the body[1] ; using touch as treatment and an opportunity to help

the patient to become aware of their reactions, and to guide movements and exercises)

c) Elements of the bond

- Nature of the rapport

(Nature of the rapport is the foundation of cooperation – with reciprocal acknowledgement of the other

person; “getting along”; a mix of professional rappor ()ethical aspects; primary focus on returning to

participation in meaningful activities) and personal rapport (related to mutual ground of e.g. having kids

in the same age)

- Respect (as an mutual acknowledgement of a person’s inherent importance or value; p. 168)

(e.g. equal respect and openness for all patients; welcoming and showing regard; being main focus of the

therapist at the moment; respect for knowledge of therapist; upholding patients’ dignity at times where

they may feel vulnerable due to e.g. physical limitations, low self-esteem or cultural, gender factors)

- Trust (often used together with respect)

(related trust in the physiotherapist as a professional being knowledgeable and having the necessary

skills; overlap of professional and personal trust; physiotherapist’s trust in the patient; especially the

physiotherapists showing their intention to help patients achieve their rehabilitation goals without

causing undo physical or psychological harm).

- Caring (as an expression of concern or regard for the well-being of another person; p. 180)

[1]. With additional education physiotherapy can move beyond a mechanical paradigm of the human body. As an expression of psychologically informed practice and a concept of “embodment”, they may learn to guide patients with e.g. tension reactions to the awareness of relationships with their emotional experiences. (Nichols et a, 2010, 2013)

1.10 Conclusion

Especially the exploration of the patients’ personal insights about their condition ànd regular feedback about their perspective and feelings about the therapeutic process play a decisive role in the development of a therapeutic alliance.

|

In the development of a therapeutic alliance an atmosphere needs to be created in which patients (Dickson, Hargie, & Morrow, 1997, p. 139): · Feel appreciated, accepted and understood · Can gain further insight into their situation · Can discuss what matters to them, regarding meaningful goals and preferred interventions · Are supported and guided in the development of action plans |

|

Reflection tip: · In which points of this blog did you recognize your communication and goalsetting steps with your patients? · Are there any areas which would you like to explore more? You may think of

Just let me know what you think: elly.hengeveld@imta.ch

Cheers, Elly |

1.11 References

Alodaibi, F., Beneciuk, J., Holmes, R., Kareha, S., Hayes, D., & Fritz, J. (2021). The Relationship of the Therapeutic Alliance to Patient Characteristics and Functional Outcome During an Episode of Physical Therapy Care for Patients With Low Back Pain: An Observational Study. Physical Therapy, 101(1): 1-9. DOI: 10.1093/ptj/pzab026.

Babatunde, F., MacDermid, J., & MacIntyre, N. (2017). Characteristics of therapeutic alliance in musculoskeletal phystiotherapy and occupational therapy practice: a scoping review of literature. BMC Health Services Research, 17: 375. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-017-2311-3.

Bishop, F., Al-Abbadey, M., Roberts, L., MacPherson, H., Stuart, B., Fawkes, C., . . . Bradbury, K. (2021). Direct and mediated effects of treatment context on low back pain outcome: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 11:e044831. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-044831.

Couët, N., Desroches, S., Robitaille, H., Vaillancourt, H., Leblanc, A., Turcotte, S., . . . Légaré, F. (2015). Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expectations, Vol 18, Issue 4. doi: 10.1111/hex.12054.

CSP. (2020). CSP Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Retrieved from Physiotherapy Framework - putting physiotherpy behaviour, values, kjnowledge & skills nto practice: https://www.csp.org.uk/system/files/documents/2020-05/CSP%20Physiotherapy%20Framework%20May%202020.pdf

Daluiso-King, G., & Hebron, C. (2020). Is the biopsychosocial model in musculoskeletal physiotherapy adequate? An evolutionary concept analysis. Physiotherapy Theory and Practie, 38(3): 373 - 389. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1765440.

Derghazarian, T., & Simmonds, M. (2011). Management of Low Back Pain by Physical Therapists in Quebec: How Are We Doing? Physiotherapy Canada, 64(4): 464-473 https://doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2010-04P.

Dickson, D., Hargie, O., & Morrow, N. (1997). Communication skills training for health professionals. 2nd ed. London: Chapmann & Hall.

Dierckx, K., Deveugele, M., Roosen, P., & Devisch, I. (2013). Implementation of Shared Decision Making in Physical Therapy: Observed Level of Involvement and Patient Preference. Phys Ther, 93(10): 1321-1330. doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20120286.

Edwards, I., Jones, M., Higgs, J., Trede, F., & Jensen, G. (2004). What is collaborative reasoning? Adv. in Physiotherapy, 6: 70 - 83 . doi.org/10.1080/14038190410018938.

Fuentes, J., Armijo-Olivo, S., Funabashi, M., Miciak, M., Dick, B., Warren, S., . . . Gross, D. (2014). Enhanced Therapeutic Alliance Modulates Pain Intensity and Muscle Pain Sensitivity in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: An Experimental Controlled Study. Phys. Ther., 94: 477-489. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130118.

Gardner, T., Refshauge, K., McAuley, J., Hübscher, M., Goodall, S., & Smith, L. (2019). Combined education and patient-led goal setting intervention reduced chronic low back pain disability and intensity at 12 months: a randomised controlled trial. Br. J Sports MEd, 0:1-9. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100080.

Godolphin, W. (2009). Shared Decision Making. Healthcare Quartelijk, 12: e186-e190. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/William-Godolphin/publication/51437687_Shared_Decision-Making/links/02e7e53b43eeab9bfb000000/Shared-Decision-Making.pdf.

Hack, T., Degner, L., & Watson, P. (2006). Do patients benefit from participating in medical decisionmaking? Longitudinal follow-up of women with breast cancer. Psycho-oncology, 15: 9-19. DOI: 10.1002/pon.907.

Hall, A., Ferreira, P., Maher, C., Latimer , J., & Ferrreira, M. (2010). The Influence of the Therapist-Patient Relationship on Treatment Outcome in Physical Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Physical Therapy, 90:1099-1191. doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090245.

Hausherr, A., Suter, L., & Kool, J. (2020). Shared decision-making in physical therapy: a cross-sectional observational study. Eur. J. of Physiotherapy, 23(6) DOI: 10.1080/21679169.2020.1772869.

Hengeveld, E., & Banks, K. (2014). Maitland's vertebral manipulation: Management of neuromusculoskeletal disorders. Vol one. 8th ed.Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

Hoffmann, T., Légaré, F., Simmons, M., McNamara, K., McCaffery, K., Trevena, L., . . . De Mar, C. (2014). Shared decision making: what do clinicians need to know and why should they bother? Medical Journal of Autralia, 35-39. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00002.

Horvath, A., & Greenberg, L. (1989). Development and Validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. J. of Counseling Psychology, 36(2): 223-233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223.

Hutting, N., Oswald, W., Staal, J., & Heerkens, Y. (2020). Self-management support for people with non-specific low back pain: A qualitative survey among physiotherapists and exercise therapists. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, Vol. 50, 102269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102269.

Jensen, G., Gwyer, J., Shepard, K., & Hack, L. (2000). Expert Practice in Physical Therapy. Phys Ther, 80:28-43. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/80.1.28.

Kamper, S., Haanstra, T., Simmons, K., Kay, M., Ingram, T., Byrne, J., . . . Hall, A. (2018). What Do Patients with Chronic Spinal Pain Expect from Their Physiotherapist? Physiotherapy Canada, 70 (1) 36-41. doi:10.3138/ptc.2016-58.

Kinney, M., Seider, J., Floyd Beaty, A., Coughlin, K., Dyal, M., & Clewley, D. (2018). The impact of therapeutic alliance in physical therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiotherapy Theory and Prctice, Online. DOI: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1516015.

Leach, E., Cornwell, P., Fleming, J., & Haines, T. (2010). Patient centered goal-setting in a subacute rehabilitation setting. Disability and Rehabilitation,, 32(2): 159-172. DOI: 10.3109/09638280903036605.

Leeming, D. (2014). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. 2nd ed. New York: Springer.

Mattingly, C., & Fleming, M. (1994). Clinical Reasoning: Forms of Inquiry in Clinical Practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

Miciak, M. (2015). Bedside Matters: A Conceptual Framework of the Therapeutic Relationship in Physiotherapy. PhD Thesis Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. Alberta: Univertsity of Alberta. Derived from; https://era.library.ualberta.ca/files/9z903246q.

Miciak, M., Mayan, M., Brown, C., Gross, D., & Joyce, A. (2018b). The necessary conditions of engagement for the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy: an interpretive description study. Archives of Physiotherapy, 8:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40945-018-0044-1.

Miciak, M., Mayan, M., Brown, C., Joyce, A., & Gross, D. (2018a). A framework for establishin connections in physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 35(1): 40-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1434707.

Moore, A., & Jull, G. (2012). Patient-centeredness. Editorial. Manual Therapy, (17) 377.

Moore, A., Holden, M., Foster, N., & Jinks, C. (2019). Therapeutic alliance facilitates adherence to physiotherapy-led exercise and physical activity for older adults with knee pain: a longitudinal qualitative study. J. of Physiother., 66 (1), 45-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2019.11.004.

Moore, C., & Kaplan, S. (2018). A Framework and Resources for Shared Decision Making: Opportunities for Improved Physical Therapy Outcomes. Phys. Ther., 98: 1022-1036. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzy095.

Myers, C., Thompson, G., Hughey, L., Young, J., Rhon, D., & Rentmeester, C. (2022). An exploration of clinical variables that enhance therapeutic alliance in patients seeking care for musculoskeletal pain: A mixed methods approach. Musculoskeletal Care, 1-16. DOI: 10.1002/msc.1615.

Naylor, J., Killingback, C., & Green, A. (2022). What are the views of musculoskeletal physiotherapists and patients on person-centred practice? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitatio, DOI: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2055165.

NICE. (2017). Shared Decision Making. www.nice.org.uk: National Institute of Health and Care Excellence.

Nicholls, D., & Gibson, B. (2010). The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 26(8): 497-510. DOI: 10.3109/09593981003710316.

Nicholls, D., Walton, J., & Price, K. (2009). Making breathing your business: enterprising practices at the margins of orthodoxy. health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 13(3): 337-360. DOI: 10.1177/1363459308101807.

Owen, M. (2022). The art of listening. Von Aeon Magazine: https://aeon.co/essays/the-psychologist-carl-rogers-and-the-art-of-active-listening abgerufen

Parry, R. (2004). Communication during goal-setting in physiotherapy treatment sessions. Clinical Rehabilitation, 18: 668 /682. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr745oa.

Pinto, R., Ferreira, M., Oliveira, V., Franco, M., Adams, R., Maher, C., & Ferrreira, P. (2012). Patient-centred communication is associated with positive therapeutic alliance: a systematic review. J of Phsyiotherapy, 58: 77-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70087-5.

Rose, A., Rosewiliam, S., & Soundy, A. (2017). Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(10: 65-75 http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.030.

Sarinopoulos, I., Hesson, A., Gordon, C., Lee, S., Wang, L., Dwamena, F., & Smith, R. (2013). Patient-centered interviewing is associated with decreased responses to painful stimuli: An initial fMRI study. Patient Education and Counselling, 90(2): 220-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.021.

Thomson, D. (1998). Counselling and clinical reasoning: the meaning of practice. Br. J. of Therapy and Rehabiliation, 5: 88-94. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjtr.1998.5.2.14221.

Thomson, D., Hassenkamp, A., & Mansbridge, C. (1997). The Measurement of Empathy in a Clinical and Non-Clinical Setting. Does Empathy Increase with Clinical Experience? Physiotherapy, 83(4): 173-180 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9406(05)66074-9.

Trede, F. (2000). Physiotherapists' approaches to low back pain education. Physiotherapy, 86, 427-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9406(05)60832-2 .

Unsgaard-Tøndel, M., & Søderstrøm, S. (2021). Therapeutic Alliance: Patients’ Expectations Before and Experiences After Physical Therapy for Low Back Pain—A Qualitative Study With 6-Month Follow-Up. Phys. Ther., 101:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab187.

WHO. (1998). Health promotion glossary. Geneva: World Health Organization.

WHO. (2001). ICF - International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organisation, WHO.

Wodak, R. (1997). Critical discourse analysis and the study of doctor-patient interaction. In B.-L. Gunnarsson, P. Linell, & B. Nordberg, The construction of professional discourse. (p. Chapter 9). New York: Routledge Publishers.

Comments